Query on PDA with emergency lifted

Published on: Sunday, March 24, 2024

By: David CC Lim

Text Size:

Signing of the Malaysia Agreement.

Why the Borneo delegates changed their minds at the CPA remains an enduring question. Ghazali in his “Memoir” gives a clue; he said he picked Stephens to head a consultative committee as:

“I became convinced that the move to form a consultative committee had to be made by someone from the British Borneo and none better than Donald Stephens.”

Together, Ghazali and Lee Kuan Yew arranged private meetings with Stephens, and managed to convince him of the necessity and viability of the Malaysia plan.

Dr Herman J. Luping in his Sabah’s Dilemma: The Political History of Sabah (1960-1994) [1994] observes:

“He [Lee] was obviously very persuasive. Stephens, the only delegate from the Borneo territories [who] was converted…Stephens had indicated during the months of May to July 1961 that he wanted Sabah to be independent first before joining Malaya in a new federation. However, he changed this stand soon after the CPA meeting in Singapore….” (p.46)

Asked why there was an abrupt change of tune among leaders in Sabah in favour of Malaysia, Former Sabah State Secretary, Sipaun cynically suggested that they [the leaders] were not in a position to think objectively for themselves. In addition, they had seen the terms agreed by Singapore and thought the process to be inevitable.

Sipaun also suspected that those leaders could be motivated by personal self-interest and the prospect of occupying important positions in government following the formation of Malaysia. (50 Years of Malaysia, Federalism Revisited, Andrew Harding and James Chin, Marshall Cavendish International, 2014 p.54.)

A more prosaic answer to the subsequent change of mind of most of the Borneo leaders is given by Poh Ling Tan in “From Malaya to Malaysia”:

“[The change] can be attributed partly to the concerted and clever campaign run by Tunku and Lee including public relations tours for political leaders of the Borneo territories to see Malaya’s rural development as evidence of what they stood to gain from federation.” (Constitutional Landmarks in Malaysia, The First Fifty Years, 1957 – 2007, Lexis Nexis, 2007, p.29).

The conventional story is that the people of Sabah had come up with the “20 points” as a condition for joining Malaysia. Sipaun however was dismissive of the “20 points”:

“Its contents reflected the standard of negotiating capacity, ability and experience of the North Borneo negotiating team. Some points are negative for North Borneo, such as point 4: The head of state shall not be eligible for election as the head of the federation. This is tying your own hands forever. Point 7 – no right of secession.

What point is that in terms of North Borneo’s interest? This is akin to going into a prison cell and locking the door and throwing the key away!”

Zainnal considers the “20 points” as “a deception”, saying that the memorandum on which they were written was just “four pieces of paper…just an understanding of the five local political parties” which were not representative of the people. The memorandum was then submitted to the Inter-Governmental Committee as “the minimum safeguards” for North Borneo to the formation of Malaysia.

Zainnal’s argument is that the “20 points” had totally misled the people of Sabah. Instead of negotiating for more state rights and autonomy from the federal, Sabah leaders until recently voluntarily bound themselves to the conditions under the “20 points” in dealing with Kuala Lumpur to the detriment of their people’s interests.

In the book, Zainnal notes ruefully, Sabah leaders are still harping on the 20 points without really understanding that the rights and safeguards given under MA63 to the two states in fact go further than those 20 points.

Zainnal also notes that G.S. Sundang of the Pasok Momogon, himself an indigenous leader, did not agree to having “minimum safeguards” but insisted on complete state rights, such as those given to Penang and Malacca.

Out of frustration, Sundang carved out three main conditions on what is today reverently called the “Oathstone”, namely; Freedom of Religion in Sabah; Land is a Sabah state matter, and Indigenous Customs and Culture must he respected and protected by the Government. To Zainnal, it is ironic that this stone is now considered by many, even those who revere the 20 points, as sacred.

Zainnal’s view is that the Sabah leaders had used the memorandum to convince the people that they had their welfare in mind, while actually using it to bargain with Kuala Lumpur for their own private benefit.

This “deception” had lulled the ordinary people into thinking that their leaders were bravely standing up for their rights, whereas their rights under MA63 were never either fully understood or enforced. Sarawak leaders appeared to be similarly befuddled or blissfully complacent until many years later in 2014 when Tan Sri Adenan Satem attained office as Sarawak’s 5th Chief Minister.

Former Sarawak State Attorney General, J. C. Fong, agrees that too much importance had been accorded to the “20 Points”:

“It is therefore, the Malaysia Agreement, and not the “20 Points” (for Sabah) and the “18 Points” (for Sarawak) which binds all the parties in the formation Malaysia, or for Sabah and Sarawak to join the new Federation. It would not be helpful towards promoting goodwill and unity in Malaysia and among Malaysians, to continually refer to a wish list contained in a “manifesto” like the “20 Points” when representatives of all parties have signed that sacred and conclusive document called the “Malaysia Agreement” to give birth to our country.” (Constitutional Federalism in Malaysia, J. C. Fong, Sweet and Maxwell, 2016 p.150).

However, Fong’s reason not to “continually refer to a wish list” in the interest of “promoting goodwill and unity in Malaysia” sounds more like a caution to not rock the boat, ignoring the glaring lack of goodwill from Kuala Lumpur in handling economic and social issues, particularly those pertaining to education and religion, unique to the two states.

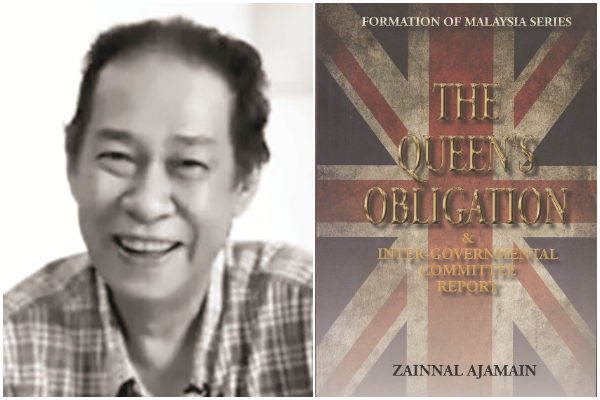

Late Zainnal Ajamain. (Pic on the right: The Queen’s Obligation book)

A contrary approach is however taken by author Sukumaran Vanugopal in his, The Constitutional Rights of Sabah and Sarawak, (Sweet and Maxwell, 2013, Chapter 3). One whole chapter is devoted to the juxtaposition between what he calls the Twenty-Point Memorandum of the Sabah Alliance and the Cobbold and IGC Reports.

The view is taken that the IGC Report elaborates what was demanded in the Memorandum, and each point in the Memorandum is dealt with in detail in the chapter.

With regard to Sarawak’s “18 Points” Leigh has this to say: “I have found no evidence that any such document was ever drafted and presented to those who were assessing whether or not the population of the Borneo states wished to be part of a larger federation.”(p.18)

In actual fact, neither the “20 points” nor the “18 points” were ever the consensus of the peoples of the two territories to form Malaysia. They were only considered as the basis for negotiations on the terms for the merger, and hence should only be treated as such.

Ghazali Shafie commented on this in his Memoir:

“Neither the North Borneo in their “twenty points” nor Sarawak in their “eighteen points” made reference to the subject [the position of the High Court of Borneo]. But the expatriate officers did, and together with the Malayans they wanted to ensure that the system of justice would continue to maintain a high standard of credibility without which a nation would flounder.”

It is clear from Ghazali Shafie’s Memoir that the Sarawak and Sabah delegates at the IGC meeting were ill equipped, either politically or economically, to negotiate for their rights.

This is understandable as most of them did not have the experience in either administrative or fiscal affairs. The colonial officers had to step in time and again to point out the crucial issues on which the delegates had to make their stand.

According to Ghazali:

“The Financial Secretary suggested that the North Borneo leaders had viewed the exercise as the formation of a true federation with some appreciable amount of powers to North Borneo.

However, the reality of the situation as seen by the Malayans was that for all intent and purpose, the Federation was a unitary state demanding a strong central government and that the Malaysia plan was merely to admit new members to that Federation.”

Ghazali called that a “momentous advice” and perhaps half expected the North Borneo delegation to walk out or call for a recess, instead, he recounted:

“Donald Stephens…took the bold step of making an appeal that the North Borneo delegation should modify its demands and that the failure of fiscal talks should not be the cause of North Borneo staying out of Malaysia.” (Ghazali Shafie, Memoir, p.318).

Ghazali added that Stephens then vouched for the sincerity of the Malayan leaders. As events transpired that was a grave error on the part of the Borneo delegates. The trust that Stephens placed on Razak was certainly a misplaced trust.

Sipaun observes regretfully: “None of our leaders at the time had tertiary education. The leader of the Muslim community, Dato Mustapha Harun, I believe, was only an office boy at the time. Donald Stephens, I was told, only reached school certificate level.

'None of our leaders at the time had tertiary education. How could you expect these leaders to deal with leaders like Lee Kuan Yew and Tunku, who were both lawyers? Malaysia came at least ten years too early!' – Sipaun

The Chinese leader at the time, Khoo Siak Chew was not a university graduate, to the best of my knowledge. How could you expect these leaders to deal with leaders like Lee Kuan Yew and Tunku, who were both lawyers? Malaysia came at least ten years too early!” (Fifty Years of Malaysia, p.58-59).

The Malayans also took advantage of the fact that the Tunku had a direct line to the British PM to disregard their suggestions or appeal to Whitehall over their heads.

Ghazali certainly did not mince his words when he describes in the Memoir how he put the colonial officers in their place on a number of occasions.

It should be noted that during this time, officers from Malaya had a free run of the state, and one would not be surprised if some of the locals in the two states were cowed, if not coerced into agreeing to the merger, or keeping quiet.

On July 23, 1963, The Straits Times reports: “The Minister Without Portfolio, Senator Khaw Kai Boh, left for Sarawak by air this morning on what he described as a “four-day liaison visit.”

Khaw Kai Boh, was the former head of the Special Branch in Singapore, thus a person to be feared. Khaw had applied for early retirement in 1959, with an ulterior motive, it transpired. Much to Lee Kuan Yew’s consternation, he was paid seventy three thousand Straits Dollars after his application was approved by State Secretary, Alan Lennox-Boyd, and later left for Malaya. He was later appointed Senator by the Tunku.

Lee Kuan Yew describes Khaw and his fellow senator, former news editor, T H Tan, in these terms in “The Singapore Story”:

“The Tunku had appointed both of them senators in the federal parliament and made Khaw a minister. They were gross, looked the fat-cats thugs that they were, and had no success with our Chinese merchant community.”(The Singapore Story, p.425).

Knowing they have the full weight and support of theTunku and thereby the British Prime Minister behind them, the Malayans were not shy of intimidating the colonial officials in the two territories. Leigh in page 61 of “Deals Datus and Dayaks” tells of the following incident:

“KL leaders deeply distrusted Ningkan and thought he was a quite unsuitable choice for chief minister and they had the right to nominate members of the state government “as they were taking over”, to quote Malayan minister and former Special Branch head, Khaw Kai Boh. In Sarawak, the British governor, Alexander Waddell refused to delay the swearing in, even by a day, insisting upon his immediate recall if overruled by London [telling London as follows]:

“I saw Khaw Kai Boh who threatened me with the Tunku’s displeasure, cajoled me on behalf of Tun Razak and pleaded with me on his own account. They distrust Ningkan and find him too outspoken and unpliable to their liking…..Apparently the Malayans had thought they had negotiated package deal and were expecting all Sarawak Alliance members to troop off to Kuala Lumpur for their instructions.”

Unfortunately there was among the delegates and leaders of the two territories too much trust in, if not deference to the Malayans.

Having raised the issue of education, which was strongly felt by all at the IGC committee meeting, the Borneo leaders meekly accepted Razak’s point that education was an “integrative force” in nation building, and that it should be a federal matter.

Stephens, who had wanted education to be a state matter, appeared flustered with that riposte from Razak, and was either unable to come up with a credible reply, or felt himself constrained, voluntarily or otherwise, by the “20 points”.

According to Ghazali: “Stephens found himself unable to depart from the mandate given under the 20 points and suggested that he would arrange for Razak to meet the local political leaders and explain to them the federal education policy.”(Memoir, p.309).

Ghazali thought the British officials had acted fairly in encouraging Razak to meet with the political leaders of North Borneo and the respective directors of education of the two territories to consider the technical aspect of placing education in the federal list. He praised the British delegates, for being “highly conscious of [their] colonial responsibility towards the peoples of the two territories” although in his opinion, Lord Lansdowne, like Lord Cobbold, had “very little political sense”.

The result was that education remains a federal matter, subject to some provisos, in particular, that there should be no application to the two territories of any federal requirements regarding religious education, and, that English would remain as the official language in the two territories for the next ten years following.

However, in the ensuing decades, due to either to ignorance, neglect or indifference of their leaders, even these safeguards given under the IGC to the Borneo territories have been eroded, with English as the medium of instruction in schools given away, gratis.

Zainnal calls education the “critical ingredient” but does not elaborate on the extent of autonomy in education granted to the Borneo territories.

However, it may be argued that the right given to the Borneo states to use English as the official language for ten years following and until their legislatures decide otherwise, presumes that English should remain as the medium of instruction until such time, otherwise that right would be rendered nugatory.

Perhaps with some foresight on the use of English in the future Malaysia, Ghazali quips:

“This [the ten-year dispensation ]of course presupposed that the bureaucrats in Kuala Lumpur could still by that time communicate in English or they would have to devise some means of communication using the English language.” (Memoir, p. 311)

It must be said, however, that the general theme of “The Queen’s Obligation” is consonant with the view that MA63 is valid, and that all the rights given to the two states are there, under Article VIII in black and white.

The book urges the state leaders to appoint constitutional, legal and fiscal experts to go through them with a fine tooth comb, and to enforce, and educate Kuala Lumpur on those rights, if necessary.

Zainnal points out that one of the rights which has not been enforced by the Sabah state government given is the “North Borneo 40% Growth Revenue Grant”, contained in Paragraph 8 under Section 24 of the IGC Report. In the beginning, this term was adhered to, and the Central government contributed RM67 million from 1964 to 1968. However, the grant was changed to “Special Grant” in 1969 and the amount fixed at RM20 million. (TQO, pp.172-175)

Zainnal also argues that the Petroleum Development Act, 1974 which was passed during the state of emergency that was declared in 1969, should be considered void ab initio. Alternatively, he argues that after the lifting of the state of emergency in November, 2011, the Act is rendered unenforceable.

Zainnal however concludes by saying that the fault in not insisting on enforcing the rights and safeguards lies partly on the people themselves:

“Some of the fault may lie with the British, partly the Central government may be blame (sic) for taking advantage of our ignorance, our innocence and gullibility. But most of all the blame lies with us for being passive, complaisant, unassuming, lack of foresight and our inability to learn in the past five decades to look after ourselves.”(TQO, p.233)

It might perhaps be an unduly severe judgment to be placed on the people, bearing in mind that the merger had been forced upon the peoples of the two territories by their colonial master at a time when they were ill-prepared to shoulder the burden of self-governance.

Evidence of this could be seen in the ensuing years and decades when the country as a whole was controlled or manipulated by the political elites in Kuala Lumpur, resulting in the deterioration of governance and the decline in almost all civil institutions.

In an article in the Journal of Contemporary Asia, historian Francis E. Hutchinson observes:

“During the Mahathir era, increasing authoritarianism had a more indirect effect on federal-state relations, through a general weakening of institutions and stifling dissent to federally pursued policies such as privatization.” (Malaysia’s Federal System: Overt and Covert Centralisation, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 2014, p.17)

The Malaysia Agreement is at risk of becoming irrelevant. According to Hutchinson, as the country’s federal system is in jeopardy; “an intricate and overlapping web of federally controlled agencies, corporations and regulatory bodies have replaced the country’s multi-leveled governance structure.” (p.17).

Whatever rights and safeguards guaranteed under the Malaysia Agreement have been easily side-stepped, as, “there are no safeguards to protect state rights from being further eroded through amendments to the constitution. Depending on the nature of the amendment, a simple majority of two-thirds majority in both the senate and the lower house is necessary.” (p.6).

Described as a “semi-democracy, pseudo-democracy or low quality democracy” in 2015, (“Pseudo-Democracy and the Malay-Islamic State”, James Chin, 2015), Malaysia seems to have borne that out in action, and broken all records in terms of wealth stolen by its own elected leaders.

If Zainnal’s forewarning had been heeded and attended to by the leadership in the two states even as late as 2015 when the book was published, it could have a salutary and restorative effect in the two states.

Unfortunately, the book can be said to have been overtaken by events in the mainland that have seen the federation as a whole spiraling downwards, overburdened by corruption, incompetence among political factions, and inter-racial and religious hangovers.

However, whatever flaws “The Queen’s Obligation” has, and it has quite a number, it must be admitted that Zainnal was a pioneer in bringing the Malaysia Agreement, with its ancillary rights and safeguards to the attention of the people and the leaders of the two states.

Though this commendation of the author is posthumous, it is hoped that he will be remembered for his part in reminding people of the real spirit of MA63.

Further, if there is a lesson to be learned from Zainnal it is that the leaders in the Borneo states themselves have to avail the states of the rights they have under MA63, a duty which they owe to their people and the discharging of which has been long overdue, and, in the light of the above, extremely urgent.

- The views expressed here are the views of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the Daily Express.

- If you have something to share, write to us at: [email protected]

ADVERTISEMENT